Another links post is up over at Demography Matters!

- Skepticism about immigration in many traditional receiving countries appeared. Frances Woolley at the Worthwhile Canadian Initiative took issue with the argument of Andray Domise after an EKOS poll, that Canadians would not know much about the nature of migration flows. The Conversation observed how the rise of Vox in Spain means that country’s language on immigration is set to change towards greater skepticism. Elsewhere, the SCMP called on South Korea, facing pronounced population aging and workforce shrinkages, to become more open to immigrants and minorities.

- Cities facing challenges were a recurring theme. This Irish Examiner article, part of a series, considers how the Republic of Ireland’s second city of Cork can best break free from the dominance of Dublin to develop its own potential. Also on Ireland, the NYR Daily looked at how Brexit and a hardened border will hit the Northern Ireland city of Derry, with its Catholic majority and its location neighbouring the Republic. CityLab reported on black migration patterns in different American cities, noting gains in the South, is fascinating. As for the threat of Donald Trump to send undocumented immigrants to sanctuary cities in the United States has widely noted., at least one observer noted that sending undocumented immigrants to cities where they could connect with fellow diasporids and build secure lives might actually be a good solution.

- Declining rural settlements featured, too. The Guardian reported from the Castilian town of Sayatón, a disappearing town that has become a symbol of depopulating rural Spain. Global News, similarly, noted that the loss by the small Nova Scotia community of Blacks Harbour of its only grocery store presaged perhaps a future of decline. VICE, meanwhile, reported on the very relevant story about how resettled refugees helped revive the Italian town of Sutera, on the island of Sicily. (The Guardian, to its credit, mentioned how immigration played a role in keeping up numbers in Sayatón, though the second generation did not stay.)

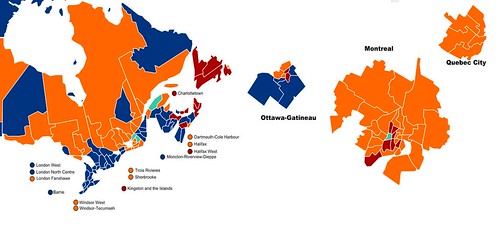

- The position of Francophone minorities in Canada, meanwhile, also popped up at me.

- This TVO article about the forces facing the École secondaire Confédération in the southern Ontario city of Welland is a fascinating study of minority dynamics. A brief article touches on efforts in the Franco-Manitoban community of Winnipeg to provide temporary shelter for new Francophone immigrants. CBC reported, meanwhile, that Francophones in New Brunswick continue to face pressure, with their numbers despite overall population growth and with Francophones being much more likely to be bilingual than Anglophones. This last fact is a particularly notable issue inasmuch as New Brunswick's Francophones constitute the second-largest Francophone community outside of Québec, and have traditionally been more resistant to language shift and assimilation than the more numerous Franco-Ontarians.

- The Eurasia-focused links blog Window on Eurasia pointed to some issues. It considered if the new Russian policy of handing out passports to residents of the Donbas republics is related to a policy of trying to bolster the population of Russia, whether fictively or actually. (I'm skeptical there will be much change, myself: There has already been quite a lot of emigration from the Donbas republics to various destinations, and I suspect that more would see the sort of wholesale migration of entire families, even communities, that would add to Russian numbers but not necessarily alter population pyramids.) Migration within Russia was also touched upon, whether on in an attempt to explain the sharp drop in the ethnic Russian population of Tuva in the 1990s or in the argument of one Muslim community leader in the northern boomtown of Norilsk that a quarter of that city's population is of Muslim background.

- Eurasian concerns also featured. The Russian Demographics Blog observed, correctly, that one reason why Ukrainians are more prone to emigration to Europe and points beyond than Russians is that Ukraine has long been included, in whole or in part, in various European states. As well, Marginal Revolution linked to a paper that examines the positions of Jews in the economies of eastern Europe as a “rural service minority”, and observed the substantial demographic shifts occurring in Kazakhstan since independence, with Kazakh majorities appearing throughout the country.

- JSTOR Daily considered if, between the drop in fertility that developing China was likely to undergo anyway and the continuing resentments of the Chinese, the one-child policy was worth it. I'm inclined to say no, based not least on the evidence of the rapid fall in East Asian fertility outside of China.

- What will Britons living in the EU-27 do, faced with Brexit? Bloomberg noted the challenge of British immigrant workers in Luxembourg faced with Brexit, as Politico Europe did their counterparts living in Brussels.

- Finally, at the Inter Press Service, A.D. Mackenzie wrote about an interesting exhibit at the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris on the contributions made by immigrants to popular music in Britain and France from the 1960s to the 1980s.